The delay to lower the voting age can only be described as a flagrant attempt to disenfranchise young voters. Where the amendment initially sparked enthusiasm and unanimous support across Parliament, the surprising hesitance its implementation has been met with signals a blow to Malaysia’s democracy.

In this article, Juliana Ganendra and Muhammad Syed will assess whether the actions of the Prime Minister, the Government of Malaysia and the Election Commission created a legitimate expectation regarding the timeline of bringing Undi18 into effect, and whether they had a valid basis to allow for this expectation to be frustrated. It concludes that a legitimate expectation had been established and any further delay to bring effect to the Act can justifiably be made the basis of legal challenge.

Facts

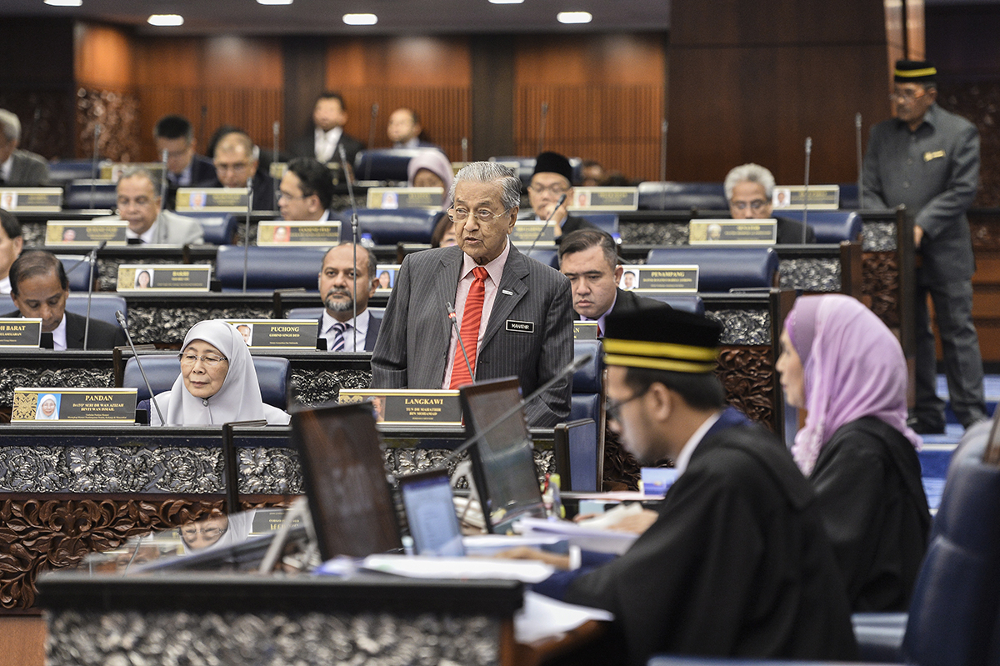

The Constitution (Amendment) Act 2019 (“Undi18 Act”) was unanimously passed in Parliament in July 2019. Malaysians rejoiced at the bipartisanship of the new government and its recognition of the youth as an important electoral component. It brought hope of a new era of Malaysian politics, symbolising a future that could and would be shaped by the younger generation.

The Undi18 Act consists of three parts, each strengthening the electorate:

- Section 3(a) lowers the minimum age for voters in federal and state elections from 21 years old to 18 years old (hereafter referred to as “Undi18”)

- Section 3(b) provides for automatic voter registration for Malaysians (hereafter referred to as “AVR”)

- Section 4 refers to the lowering minimum age for elected representatives in federal and state elections from 21 years old to 18 years old

Upon enacting the law, the Pakatan Harapan government and Election Commission (EC) had expressed their joint view that the implementation of the Act was due to be completed by July 2021 at the latest. Even after the change in government in March 2020, this timeline was maintained by the new Perikatan Nasional government and the EC.

However, in March 2021, the EC announced that because it planned to implement AVR and Undi18 simultaneously, the Act would only come into effect in September 2022. Among the reasons cited as barriers to implementing the Act were the onset of the pandemic and logistical issues with the AVR. This delay caused a deviation from the previous timeline, triggering an uproar among the public. It heightened fears that the Government was attempting to ignore and silence the youth in the midst of an unstable political climate.

In response, members of the UNDI 18 organisation applied to judicially review the Government and EC’s refusal to bring into force the Undi18 constitutional amendment by July 2021. Their application was made against the Prime Minister, the Government of Malaysia and the EC (“the Respondents”) in the High Court of Kuala Lumpur and High Court of Kuching.

The remainder of this article will evaluate the “breach of a legitimate expectation” ground for the judicial review. Given that the Malaysian Federal Court in Majlis Perbandaran Pulau Pinang v Syarikat Berkerjasama-Sama Serbaguna Sungai Gelugor [1999] 3 MLJ 1 accepted the English approach to legitimate expectations, this article will primarily rely on the more developed English case law on the doctrine.

What is a legitimate expectation?

Politicians have a reputation for making empty promises. People reluctantly accept it as part of the nature of political dealings. “Legitimate expectation” judicial reviews challenge that understanding and forces legal accountability for actions and statements made. Notably, the expectations are not law themselves, but create an actionable basis in judicial review. As a result, the court serves as an overseer of the executive by ensuring that, in specific circumstances, the Government cannot simply resile from its promises.

Judicial review for breach of legitimate expectations is grounded on principles of fairness. Namely, that it would be unfair to allow a public body to not fulfil a promise made to individuals and groups of people. It also concerns broader principles of legal certainty – individuals should be able to trust and rely on what public authorities tell them. However, the proximity of many such ‘promises’ to matters of politics makes the courts cautious to enforce these promises without strong justification.

What is necessary for a “legitimate expectation”?

The key consideration in legitimate expectation review is how the statements would be reasonably understood by the relevant party to whom it was made. The strength of the undertaking must be “clear, unambiguous and devoid of relevant qualification” (R v Inland Revenue Commissioners, ex p MFK Underwriting Agencies Ltd [1990]).

A key factor is the authority of the person making the statement, which gives recognition to the need for representatives of public authorities to act responsibly and reliably. The converse is equally true. For example, in R v Department of Education and Employment, ex p Begbie [2000], undertakings by opposition politicians during an election campaign did not create a legitimate expectation, and instead had to be merely politically enforced.

There has been inconsistency in the courts about whether a challenger must establish that they relied on the promise to their detriment. Lord Carnwath considered detrimental reliance a necessity in United Policyholders Group v Attorney General of Trinidad and Tobago [2016]. However, this had the effect of undermining the usefulness of legitimate expectation review: the applicants may not have the resources to act on the expectation, but their treatment still unfairly disregards their dignity and autonomy. Given this, Lord Kerr’s dicta in Re Finucane’s Application for Judicial Review (Northern Ireland) [2019] is more convincing:

“A recurring theme of many of the judgments in this field is that the substantive legitimate expectation principle is underpinned by the requirements of good administration. It cannot conduce to good standards of administration to permit public authorities to resile at whim from undertakings which they give simply because the person or group to whom such promises were made are unable to demonstrate a tangible disadvantage.”

Did the statements made by the EC and Ministers create a legitimate expectation?

It is convincing that the statements made by the EC and Ministers created a legitimate expectation. The Respondents had the requisite authority to make those statements, with the EC having specific purview over changes in voting law. Therefore, it is understandable to expect that the Respondents would provide the most accurate information regarding when Undi18 would come into effect. The Respondents were also explicit and unreserved about the implementation of the Undi18 Act by July 2021. The issue of Covid-19 and the technical restraints of AVR were only raised later.

The Applicants did rely on those statements as articulating basic principles of voting rights and democracy. Consequently, it would be appropriate to adopt Lord Kerr’s approach to reliance and thereby recognise the inherent importance of constitutional rights, the legitimate role of 18 to 20 year olds in participative democracy, and the unfairness of delaying the Applicants right to exercise these rights.

As a result, it was reasonable for 18 to 20 year olds to expect that their right to vote would come into effect by July 2021, and this expectation amounted to a “legitimate expectation” in law.

When can a legitimate expectation be validly frustrated?

The law recognises the discretion of public bodies to make decisions weighing logistical and political interests. As a result, public bodies may deviate from a legitimate expectation where the impugned decision requires a balance of competing policy interests, and the decision-maker has provided an adequate justification for its change in position. This consideration was explained in R v North and East Devon Health Authority, ex p Coughlan [2001], where the UK House of Lords stated:

“There was no overriding public interest which justified [the frustration of the Applicant’s legitimate expectation]. In drawing the balance of conflicting interests the court will not only accept the policy change without demur but will pay the closest attention to the assessment made by the public body itself. Here, however, as we have already indicated, the Health Authority failed to weigh the conflicting interests correctly.”

As a result, the court will evaluate the specific circumstances of each case to decide whether the public authority was justified in frustrating the legitimate expectation.

In R (Bibi) v Newham London Borough Council [2001], the UK Court of Appeal held that an established legitimate expectation must be given adequate weight in the decision making which may lead to its frustration, and therefore ordered the local authority to reconsider the matter with due account of the legitimate expectation. Notably, the court requires the public authority to have placed great importance on the legitimate expectation in the decision making process.

In ex p Coughlan, the House of Lords established that merely financial obstacles would be insufficient to justify not doing what was promised. Thus, the courts undertake a balancing exercise between the legitimate expectation and the other interest, with weighted importance on the legitimate expectation, to decide if a public authority can frustrate the expectation.

Was it justified for the Government to frustrate the legitimate expectation created?

In the Undi18 case, the Respondents’ decision-making process was flawed and unconvincing. Three justifications were provided for the delay in implementing the Undi18 Act. As will be shown, none were valid.

- Amendments had not yet been made to subsidiary legislation:

“This Constitution is the supreme law of the Federation and any law passed after Merdeka Day which is inconsistent with this Constitution shall, to the extent of the inconsistency, be void.”

It is unnecessary to make amendments to subsidiary legislation. The Constitution is the supreme law and any inconsistencies in other legislation is impliedly repealed, as established in Article 4(1) of the Federal Constitution:

That said, even if the Respondents’ claim was credible, the inconsistent legislation they referred to can be amended without the passing of an Act of Parliament. It falls within the ambit of the Government’s power to amend the Elections (Registration of Electors) Regulations 2002 so any substantive amendment would be part of the executive’s duty to effectuate the legitimate expectation anyway.

- The Covid-19 pandemic and Movement Control Orders:

The Covid-19 Pandemic and first Movement Control Order began in March 2020, and yet the Respondents continued making representations until March 2021 that the Undi18 Act could be implemented by July 2021. It is clear that when these later representations were made, the Respondents were aware and should have considered any impacts that Covid-19 and the Movement Control Order might have on their proposed timeline. For this reason, citing the pandemic as a reason for the delay of Undi18 lacks merit because consistent representations which established a legitimate expectation were still made up to a year after the first Movement Control Order.

- AVR logistical issues:

Of the three reasons submitted by the Respondents, the third comes closest to being persuasive. The Respondents insist that Parliament intended for Undi18 to be implemented simultaneously with AVR, so the logistical issues that come with enforcing AVR has delayed Undi18 from coming into effect.

Indeed, the plain meaning of Section 3 reveals that Undi18 and AVR are supposed to come into effect together as per Section 1(2). This is a point that must be conceded due to Section 43(b) of the Interpretation Acts 1948 and 1967.

However, what can be questioned is whether having accurate voter data is an “overriding public interest” that justifies breaching the legitimate expectation regarding Undi18 implementation. The Respondents failed to recognise that the delay in implementing Undi18 would contravene the constitutional right to vote granted to millions of 18-20 year olds, thereby undermining Malaysia’s democracy. Any logistical issues regarding the AVR are long-standing and have been present since the Undi18 Act was passed in 2019. Steps should have been taken earlier to address the problem, and the Respondents’ representations about implementation timing should have considered this issue.

The Respondents have no adequate justification for frustrating the legitimate expectation of millions of 18-20 year olds regarding the implementation of the Undi18 Act. Although the Respondents claim to be protecting the legitimacy of Malaysia’s democracy, they have instead undermined democracy.

Conclusion

In the most recent twist to the saga, the former Prime Minister Tan Sri Muhyiddin Yassin’s press conference on 14 August 2021 revealed that the Respondents were not truly faced with obstacles in the implementation of Undi18. In a final plea for support, after losing a majority in Parliament, he offered to implement Undi18 without AVR by tabling another bill in Parliament this September. This was a case of too little too late.

Understood properly, his offer undermined the entirety of the Respondents’ submissions, which relied on the obstacles to the implementation of the act being intractable. Instead, the former PM’s statement reveals them to be of the government’s own choice. By politicising something as fundamental to democracy as voting, the Respondents have defied the rule of law and suppressed young voters, failing to recognise their personhood. The former PM’s final attempt to retain power will always be remembered by Malaysians as a betrayal of the principles fundamental to the Constitution.

The right to vote for 18 to 20 year olds is not a political bargaining tool nor a logistical burden. Instead, it is now their constitutional right – it is time for Undi18 to be recognised and treated as such.

Juliana Ganendra and Muhammad Syed are reading law at Cambridge University and share an interest in public and human rights law. Juliana has interned at the Court of Appeal and Federal Court where she witnessed landmark constitutional judgements, including the “Bin Abdullah” case. Muhammad is currently an intern at UNDI18 and the chief editor of the Cambridge University Human Rights Journal.

Our thanks to Shukri Shahizam, Datin Shalini Amerasinghe and Dato’ Malik Imtiaz Sarwar for their comments on an earlier draft. All errors and omissions remain ours.