Introduction

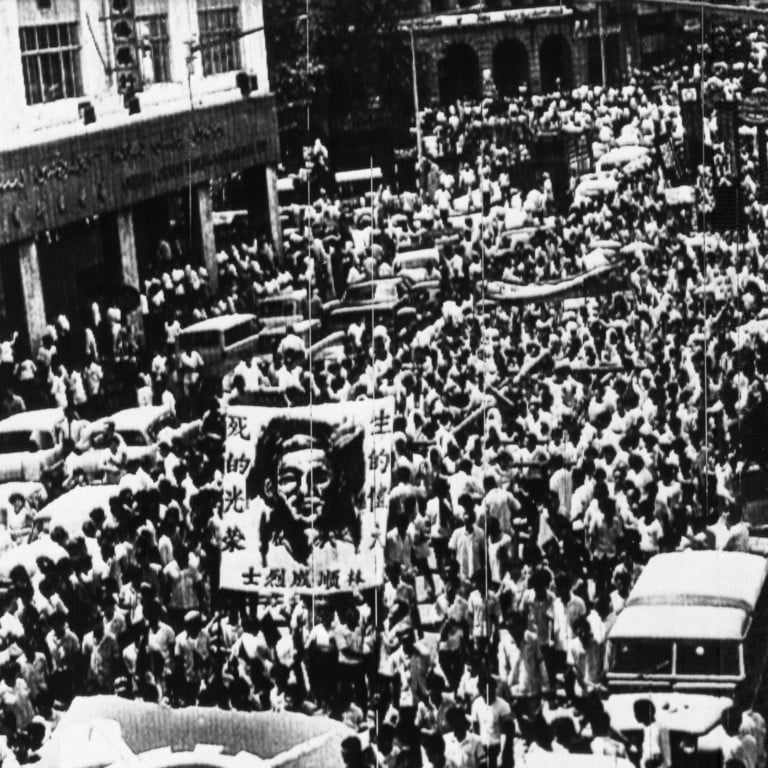

The tremor of emergency grips the Malaysian soil once again. After witnessing yet another onslaught of COVID-19, it seems likely that a state of emergency shall be declared. However, should this declaration take place, it is also timely for another glaring reason – it would arm the Executive with a legal Infinity Gauntlet that could ‘snap’ away any and all prospects of political upheaval. But to most Malaysians, we have not lived through a state of Emergency. A state of emergency had only been declared twice in our nation’s history – first during the 1964 confrontation with Indonesia, and second during the May 13th racial riots. Is this behemoth known as a Declaration of Emergency so frightful? Is the Cabinet empowered to do any and everything it desires? To what limit may emergency ordinances be promulgated? What happens to our fundamental liberties? This article attempts to explain the legal characteristics and effects of a state of emergency.

Definition of an Emergency

Article 150 of the Federal Constitution (“FC”) houses the power to declare an emergency. Under Article 150(1), the term “emergency” refers to threats to the security, economic life or public order of the federation or any part thereof. In the case of Stephen Kalong Ningkan v Tun Haji Openg [1968] 2 MLJ 238, the Privy Council had broadened the conceptual perimeter of emergency by declaring that “emergency” is not confined to the unlawful use or threat of force. It includes wars, famines, earthquakes, floods, epidemics and collapse of civil government.

Who May Declare an Emergency?

In the decision of Stephen Kalong Ningkan, the Privy Council ruled that the federal power to declare an emergency rests with the YDPA, who shall act in accordance with the advice of the Prime Minister. This is pursuant to a harmonious reading of Article 150 with Article 40(1) FC, which thereby renders the YDPA bound and subjugated to the dictations of the Prime Minister.

Duration of Proclamation

A common question which may arise is how long shall a proclamation of emergency last. Before a constitutional amendment in 1960, the FC provided through Article 150(3) that a proclamation of emergency shall cease two months after it was issued unless it is revoked earlier by Parliament. This is known as a sunset clause. Subsequent to a constitutional amendment, this sunset clause was removed, and therefore a proclamation would have gone on indefinitely until it is ceased by one of the following manners: (i) the YDPA revokes it; or (ii) the two Houses of Parliament annuls it by resolution when in session.

Effect of an Emergency

The broad effects of an emergency on the organs of government may be surmised into three different headings.

First, the declaration of an emergency shall extend the legislative powers of Parliament considerably. Such extension is owed to Articles 150(5) and (6) FC:

(5) Subject to Clause (6A), while a Proclamation of Emergency is in force, Parliament may, notwithstanding anything in this Constitution make laws with respect to any matter, if it appears to Parliament that the law is required by reason of the emergency; and Article 79 shall not apply to a Bill for such a law or an amendment to such a Bill, nor shall any provision of this Constitution or of any written law which requires any consent or concurrence to the passing of a law or any consultation with respect thereto, or which restricts the coming into force of a law after it is passed or the presentation of a Bill to the Yang di-Pertuan Agong for his assent.

(6) Subject to Clause (6A), no provision of any ordinance promulgated under this Article, and no provision of any Act of Parliament which is passed while a Proclamation of Emergency is in force and which declares that the law appears to Parliament to be required by reason of the emergency, shall be invalid on the ground of inconsistency with any provision of this Constitution.

Essentially, Parliament’s power to legislate has been broadened in the following manner:

- Parliament is no longer required to consult with states or any other authority outside of Parliament in legislation;

- The consent of the Conference of Rulers (Majlis Raja-Raja) and the Governors of Sabah and Sarawak is not needed;

- Emergency legislations can be enacted with a mere simple majority of those present and voting, and not by special majority;

- Judicial review on constitutional grounds is muted by Article 150(6) which states that no provision of an emergency law shall be inconsistent with the Constitution;

- There shall be no judicial review of emergency legislation by virtue of Article 150(8) FC;

- Parliament may delegate its authority to any other subsidiary authority (Eng Keock Cheng v PP [1966] 1 MLJ 18) and Johnson Tan Hang Seng v PP [1977] 2 MLJ 66)

Hence, Parliament is empowered to legislate in a much more liberated manner, and whatever law that is promulgated under the name and style of an emergency legislation is immunized from judicial oversight.

Second, if the two Houses of Parliament are not sitting concurrently when emergency is declared, the King acquires power to legislate. He is empowered under Article 150(2B) to promulgate ordinances having the force of law. According to the judgment of PP v Ooi Kee Siak [1971] 2 MLJ 108], His Majesty’s power to promulgate ordinances is as wide as that of Parliament.

Third, there is an extension of executive powers of the federal government. When a proclamation is in force, the executive authority of the federation extends to any matter within the legislative authority of a state. Further, under Article 150(4) FC, the federal government can give directions to the states or any of its officers. This effectively means that the constitutional separation between the federal and the state executive can be ignored. A case in point is Najar Singh v Government of Malaysia [1976] 1 MLJ 203, where the Privy Council held that the delegation of the entire executive authority of Malaysia by the YDPA to the Director of Operations by the Emergency (Essential Powers) Ordinance No 2 of 1969 was valid.

Control of Emergency Powers

The broad definition of an emergency and the ouster of judicial review suggests an almost unlimited exercise of emergency powers. But of course, there are limitations here and there. First, there are preconditions to the power to promulgate emergency ordinances, as stipulated under Article 150 (2B) FC: (i) there must be a proclamation of emergency; and (ii) the two Houses of Parliament must not be in session concurrently. But nevertheless, the practicality of these requirements does not impose much fetter on emergency powers.

Next, there are several substantive limitations to emergency powers in the FC. Article 150(6A) FC states that the power of Parliament and of the Yang di-Pertuan Agong does not extend to matters of Islamic law, custom of the Malays, native law or custom in Sabah and Sarawak, religion, citizenship and language. Then, Article 151 FC states that all emergency legislation has to comply with the requirements under this provision, which deals with safeguards for preventive detainees.

Article 150(7) FC also stipulates that once an emergency comes to an end, any laws made during the emergency will cease to have effect after a grace period of 6 months.

The constitution also provides for a form of parliamentary control. While Article 150(3) FC stipulates that a proclamation of an emergency shall be laid before both Houses of Parliament, this mechanism of parliamentary control is a white elephant. This is usually ineffective as the majority of seats in Parliament are held by those from the same political party as the executive, meaning that they won’t oppose its actions in an act of solidarity and party loyalty. Besides, there is also no obligation imposed on the executive to summon Parliament because the executive may suspend the operation of Parliament indefinitely. As for judicial control, the insertion of Article 150(8) FC effectively removes any semblance of judicial oversight on emergency laws that were promulgated, save for the fetters provided in Article 150(6A).

Conclusion

To answer an earlier question, yes – this behemoth known as the Declaration of Emergency is frightful. It is a sleeping giant which, once awoken, will grip the lives of all Malaysians. while the rule of law fell into an indefinite slumber.

It is hard to resist quoting Lord Acton at this time and hour: “power corrupts, and absolute power corrupts absolutely.”

If we were to have our 3rd state of emergency, let it be inscribed in the footnotes of our history books – that this emergency came from the doors of the Sheraton.