Introduction

The FC recently delivered its judgment for the case of Maria Chin Abdullah v Director General of Immigration.

In a 4-3 split, the FC has negated the existence of the basic structure doctrine in our Federal Constitution. The majority judgment delivered by Rahman Sebli FCJ has reversed decades of development in the landscape of Malaysian constitutional law.

This brief write-up shall attempt to explain the backdrop and effects of this decision.

The Basic Structure Doctrine in a Nutshell

The basic structure doctrine, in essence, establishes that there are certain features within the Constitution that are fundamental and cannot be amended nor removed by virtue of a legislation passed by Parliament. These features are deemed to form the basic fabric of our nationhood, and should be accorded the highest regard.

Hence, it is without doubt that the basic structure doctrine plays a vital role in the legal machinery of our nation. Our fundamental liberties, the notion of separation of powers, judicial power, democracy have been recognised and protected as basic features of our Constitution that cannot be encroached by federal law.

The Constitutional Amendment of 1988

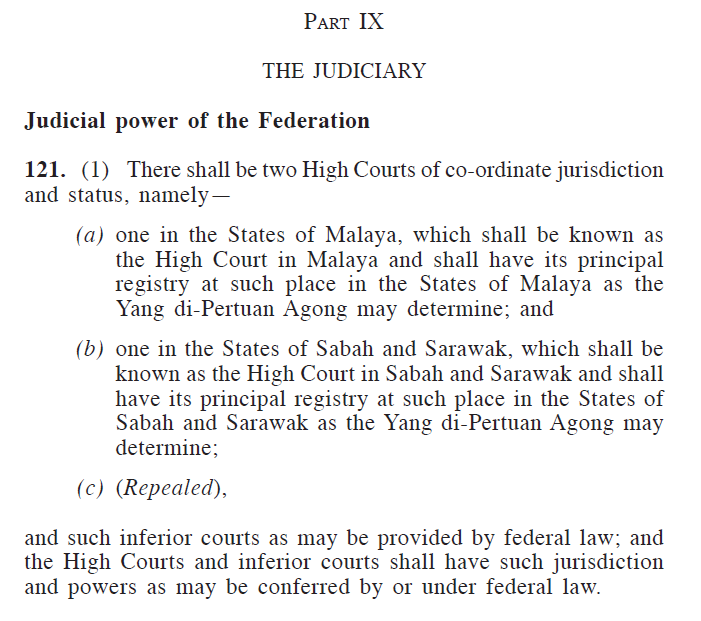

In wake of the 1988 Judicial Crisis, a series of constitutional amendments were promulgated by Parliament. One of such amendments include the amendment to Article 121(1) of the Constitution. Here, Parliament amended the wordings of Article 121(1) to remove the words “the judicial power of the Federation shall be vested in two High Courts”, and substituted it with “the High Courts and inferior courts shall have such jurisdiction and powers as may be conferred by or under federal law.”

Essentially, the amendment has removed judicial power from the courts. This interpretation of the amended Article 121(1) of the Constitution was preferred by the FC in the case of Kok Wah Kuan.

The Return of Judicial Power and the Basic Structure Doctrine

Zainun Ali FCJ through the decision of Semenyih Jaya rectified the interpretation of Article 121(1). Her Ladyship opined that the amendment to Article 121(1) could not be read in such a narrow manner as it would be manifestly inconsistent with the supremacy of the Federal Constitution in Article 4(1). It was then concluded that judicial power and separation of powers form the basic structure of the Constitution.

Then, in Indira Gandhi, Zainun Ali FCJ again expounded that it is ‘beyond a shadow of doubt’ that judicial power is vested in the High Courts, and that judicial powers such as judicial review, the principles of separation of powers, the rule of law, and the protection of minorities are parts of the basic structure of the Constitution. Her Ladyship also critically observed that the power of judicial review is essential to the role of courts and is inherent in the Constitution.

Lastly, Richard Malanjum CJ’s judgment in Alma Nudo Atenza further bolstered the decisions of Semenyih Jaya and Indira Gandhi. In its judgment, the court found that constitutions based on the Westminster model are drafted based on the principle of separation of powers, and this logically infers that these provisions surely intend to confine the exercise of legislative, executive and judicial power with the respective branches of government. As such, the absence of express recognition of separation of powers within the Federal Constitution does not mean that it isn’t fundamental.

From this trilogy of cases, the basic structure doctrine functions as a protective shield to the notion of judicial power. With that, the judiciary is fortified in its role as an independent branch of government that is tasked with the interpretation of laws and supervision of executive acts.

The Demise of the Basic Structure Doctrine?

Now we return to the FC’s decision in the case of Maria Chin.

In this case, Maria Chin sued the Director of Immigration (“DGI”) for his decision to bar her from travelling to Korea. However, this challenge was opposed by the Government by virtue of s. 59 and 59A of the Immigration Act. These provisions have the effect of denying any court the power to review the DGI’s decision, and also to deny the right to be heard before any executive decision was made by the immigration authorities. Consequently, the constitutionality of these provisions were challenged for violating the basic structure doctrine.

Rahman Sebli FCJ held that the basic structure doctrine is an Indian concept that has no place within our local constitutional jurisprudence. His Lordship did so by holding that the expositions on the basic structure doctrine found in Semenyih Jaya, Indira Gandhi and Alma Nudo Atenza were mere obiters (observation by judge that is unnecessary), thereby having no binding legal effect. With that, the basic structure doctrine has fallen.

Without the protective shield of the basic structure doctrine, the next piece of the domino is the notion of judicial power. His Lordship adopted a textualist approach to the interpretation of Article 121(1), and held that judicial power can be limited by Parliament. And because of that, the court upheld the ouster clauses’ constitutionality.

The decision of Rahman Sebli FCJ was met with strong opposition. Tengku Maimun CJ’s dissenting judgment that is supported by Nallini FCJ and Harmindar FCJ, held that sections 59 and 59A of the Immigration Act were unconstitutional and void for, among others, violating the basic structure doctrine entrenched in the Constitution.

Despite this, the majority judgment stands with the force of law. No matter the strength of the dissenting judgment, it has no legal effect, and can only hope to appeal to the intelligence of a future judge.

Hence, the FC in Maria Chin’s case may have spelled an end to the basic structure doctrine.

Conclusion

The basic structure doctrine is a recently adopted concept which preserves and protects the rule of law. Its untimely demise has sent a shockwave of grief to all members of the legal fraternity

The cases of Semenyih Jaya, Indira Gandhi and Alma Nudo Atenza restored the basic structure doctrine and the notion of judicial power in Malaysia. This trilogy of cases once marked the crescendo of judicial independence, but is now reduced to a memory of greener pastures.

Until another appeal concerning the basic structure doctrine and the notion of judicial power arises, it shall remain buried indefinitely till then.