There are blog posts and social media messages circulating lately which suggest that all Perikatan Nasional politicians who have been appointed to GLCs would be automatically disqualified from being MPs.

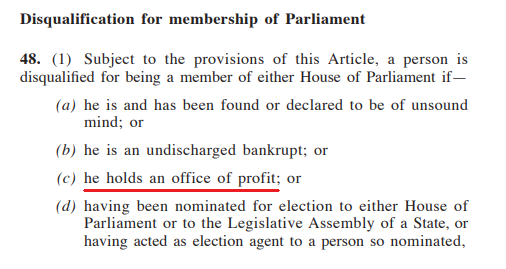

They make reference to Article 48(1)(c) of the Federal Constitution, reproduced here as follows:

These well-intentioned authors equate GLC Chairmanship or director-ship as an “office of profit”, which is the criteria for disqualification in Article 48(1)(c). On its surface, this seems like a reasonable conclusion to make.

But, in my respectful view, this is not the correct position in law.

The Actual Meaning of the Term “Office of Profit”

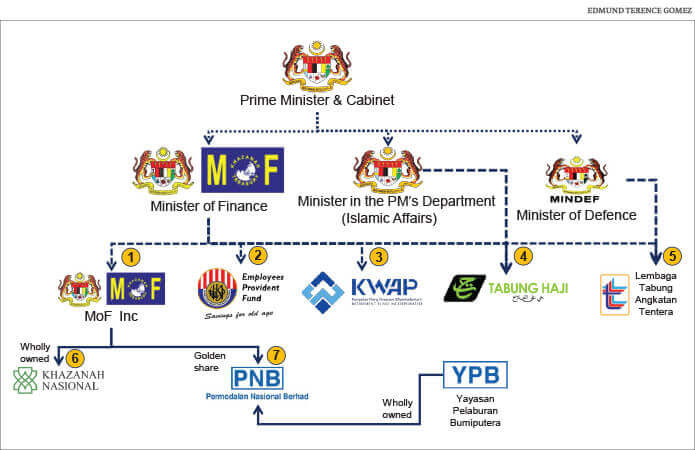

Pic Credits: The Edge

To the ordinary person, the term “office of profit” has very wide connotations and includes any position where there is a monetary compensation.

However, the term “office of profit” under the Constitution has a very specific meaning.

The first rule in interpreting the Constitution is that the Constitution must be read as a whole, and each provision should – to the best one can – be given effect.

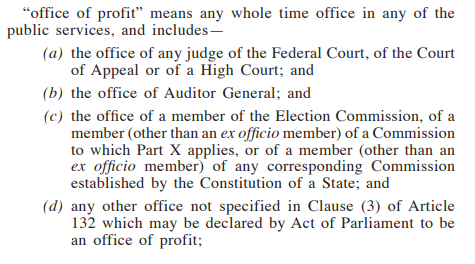

In this regard, Article 160 defines “office of profit” very specifically as follows:

In general, the term “office of profit” in the Constitution only covers certain public service positions. Thus, an MP only loses his seat in Parliament if he occupies the following positions:

(A) Any whole time office in any of the public services;

(B) A Judge of the superior courts;

(C) Auditor-General;

(D) A member of the Election Commission, Judicial & Legal Services Commission, Public Services Commission, Police Force Commission, Education Services Commission (except being an ex-officio member);

(E) A member of any corresponding Commission established by a State Constitution (except being an ex-officio member); or

(F) Any other office not specified in Article 132(3) which may be declared by Act of Parliament to be an office of profit.

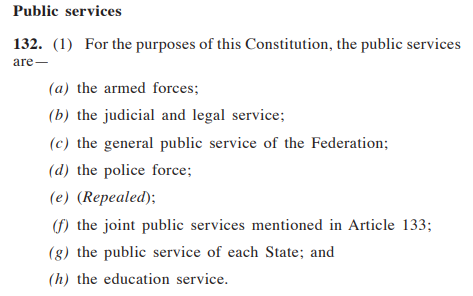

Insofar as category (A) is concerned, “public services” also has a specific meaning under the Constitution. It can be found at Article 132(1), which reads:

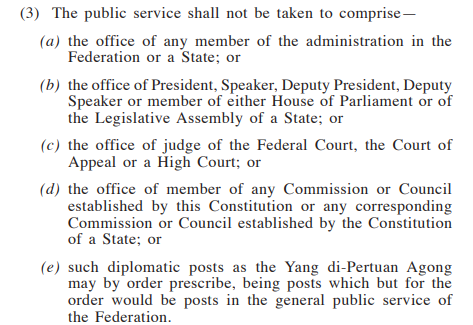

On the other hand, Article 132(3) lists down what positions are NOT considered “public services” under the Constitution:

As for category (E), in my memory, Parliament has not passed any Act to declare an office to be an “office of profit”. Hence, this category is unlikely to be invoked.

As one can observe, a GLC Chairmanship or director-ship does not appear to fall into any of the category of offices in (A) to (F) above. Therefore, in my view, the position in law is that MPs are not disqualified pursuant to Article 48(1)(c) if there are appointed to GLCs.

“Office of Profit” Under The Indian Constitution

There are, of course, many cases in India which have held what the term “office of profit” entails under the Indian Constitution.

In 1964, the Indian Supreme Court in Gurugobinda Basu v Sankari Prasad Ghosal & Ors 1964 AIR 254 ruled that the test for determining “office of profit” is the test of appointment. Some factors which will be analysed are: (i) whether the government is the appointing authority, (ii) whether the government has the power to terminate the appointment, (iii) whether the government determines the remuneration, (iv) what is the source of remuneration, and (v) the power that comes with the position.

However, there is latitude for the judiciary in India to set out the above tests only because the term “office of profit” is not defined under the Indian Constitution, in the manner the Malaysian Federal Constitution has in Article 160.

Hence, it is unlikely that Indian cases would be persuasive under Malaysian law.

A Question of Conflict of Interests, Ethics & Economic Confidence

Pic Credits: The Edge

But one must never mistake legality with morality.

In principle, an MP as part of the Legislature should not hold positions which the Executive controls. Otherwise, that MP would be beholden to the Executive, thereby failing to exercise his/her duties properly and independently as an MP to hold the Executive accountable.

The Indian Supreme Court in Ashok Kumar Bhattacharya v. Ajoy Biswas & Ors 1985 SCR (2) 50 had this to say: “The true principle behind this provision…is that there should not be any conflict between the duties and the interest of an elected member…If such a person is holding an office which brings him remuneration and the Government has a voice in his continuance in that office, there is every likelihood of such person succumbing to the wishes of Government”.

In today’s climate, the appointment of MPs as heads of GLCs reflects an even more pernicious problem. It does not take a genius to deduce that GLC positions are treated as commodities in order for the Prime Minister to secure his majority in Parliament. Professor Terence Gomez has written widely on this.

One must also not forget that GLCs own almost half the shares in the Malaysian stock market and are key players in a whole range of economic sectors. In a country facing recession amidst Covid-19, GLCs play a key role in revitalising the economy. It is imperative that qualified full-time heads lead and provide critical direction to the GLCs, instead of politicians who have many other distracting priorities.

The other fear is that this would usher back the culture of corruption the people have voted overwhelmingly against in the 14th General Elections.

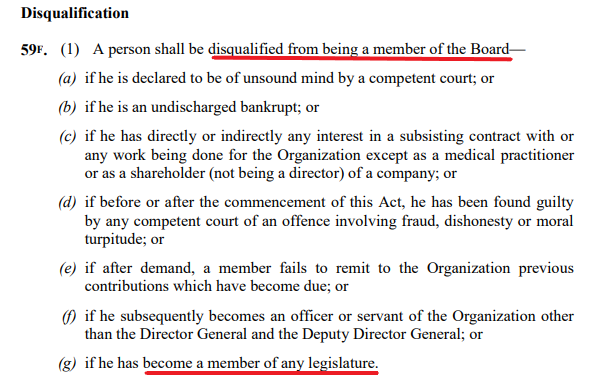

Moving forward, Parliament should seriously consider enacting laws to prevent MPs from occupying GLC positions. Section 59F(g) of the Employees’ Social Security Act 1969 is an example of such legislative far-sightedness:

Corporate Malaysia missed a golden opportunity post-9th May 2018 to weed out the decades-old culture of cronyism & patronage, and I fear that we may never witness such a moment again.