As a follow-up to Lim Wei Jiet’s timely post titled ‘1-Day Parliament Sitting: Motive, Machinations & Lessons from UK’s Prorogation Controversy’, this post will analyse in greater depth the procedural mechanisms which would likely be relevant to the effectuation of the government’s proposed one-day-session of the Dewan Rakyat. It will argue that a majority opposed to the government’s plans will have the ability to prevent it from being turned into reality and, consequently, that the government cannot unilaterally escape parliamentary accountability.

Facts

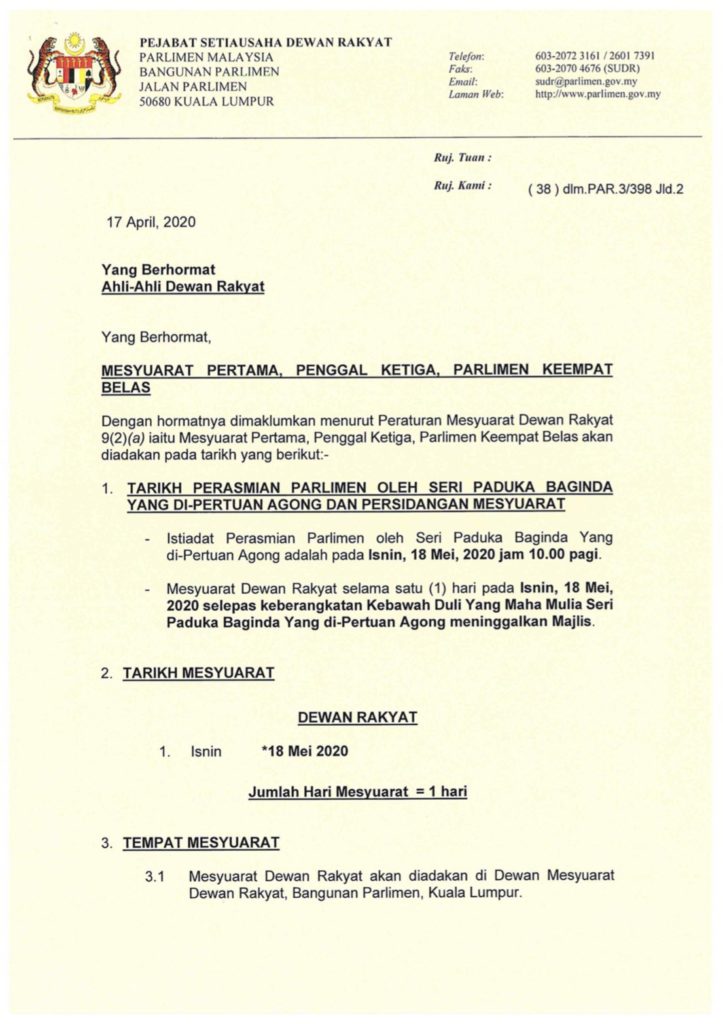

On 17 April 2020, the Secretary of the House of Representatives notified Members of the Dewan Rakyat that the House will be called for a one-day-long sitting on 18 May 2020. In his letter, the Secretary stated that the agenda for the day would be limited to an officiation of the 1st Meeting of the 3rd Session of the 14th Parliament by the Yang di-Pertuan Agong, and for debate on ‘Government Bills and Motions only’.

Accordingly, he stated that there will be no time allocated for either oral answers to questions under Standing Order 22, Minister’s Question Time under Standing Orders 24 and 24A, motions under Standing Orders 17, 18, 27 or 49, or other motions from MPs.

In ordinary circumstances where the government’s majority in the Dewan Rakyat is well known and well defined, the Secretary’s statement of a planned agenda for the Dewan Rakyat’s sitting would be nothing out of the ordinary. However, the fact that the Perikatan National government’s parliamentary majority – if it exists – is uncertain calls into question the import of the Secretary’s statement.

The Standing Orders and the Order of Business

Article 62 of the Federal Constitution prescribes that the two Houses of Parliament, the Dewan Negara and the Dewan Rakyat, ‘shall regulate [their] own procedure’. In the Dewan Rakyat, procedure is regulated by the Standing Orders which are enforced by the Speaker (or a Deputy in their place) as presiding officer of the Dewan Rakyat.

The day-to-day procedures of the Dewan Rakyat are dictated by SOs 12 and 14. SO 14 specifies the Dewan Rakyat’s standard Order of Business, which includes, in order of precedence and among other things, Minister’s Question Time, urgent motions, ministerial statements, and public (i.e. non-government) business.

This order is subject to SO 14(2), which allows a Minister to, at any time, table a procedural motion that the Dewan Rakyat conducts its ‘business out of the regular order’, which ‘shall take precedence over all business’.

While SO 14 specifies the content of a sitting, SO 12 specifies its timing. SO 12(1) states:

Each sitting of the House shall begin at 10.00 a.m. and continue until 1.00 p.m. and resume at 2.30 p.m. and continue until 5.30 p.m. or the earlier completion or deferment of business on the Order Paper

Similar to SO 14, it also allows for a Minister to, at any time, table a motion that the Dewan Rakyat’s time of sitting be varied from the default of 10am–5pm schedule.

Government Control of the Timetable

As Malaysia is a country which practices a Westminster-style government, the government in office has priority in parliamentary procedure. This is due to both principled and practical reasons. On principle, a democratically elected and representative government ought to have the ability to attempt to enact its legislative agenda, and to have the opportunity to do so before any other collection of MPs.

Even if the government’s priority were not recognised by the Standing Orders, it would be inevitable that, in practice, it would wrest priority over any other individual MP or group of MPs. This is because the government is constituted by its Prime Minister’s ability to command a majority in the Dewan Rakyat. Consequently, the government as a majority of MPs in the Dewan Rakyat would be able to exert a decisive influence in the Dewan Rakyat, whether by voting down other MPs’ procedural motions, bills, or (in an extreme case) by amending the Standing Orders.

As such, the prioritisation of Ministers’ procedural motions to timetable the Dewan Rakyat’s business is not unobjectionable per se and is, if anything, a rule that generally enhances the efficiency of Dewan Rakyat proceedings.

Under normal circumstances, procedural motions under SOs 12 and 14 are wholly unexceptional. As they can only be tabled by government Ministers and the government, by definition, almost always has a majority in the Dewan Rakyat, there is no reason to entertain the possibility that those motions would fail.

Loss of Government Control

Of course, motions to control the parliamentary timetable are only unexceptional so as long as the government has a majority to pass them.

Notably, a government may lack such a majority without being toppled. This can happen even in cases where a government retains the confidence of the Dewan Rakyat, such as when some government MPs have confidence in the Prime Minister but object to a particular timetable.

Alternatively, a government may lack a majority, but has yet to lose a formal vote of confidence.

A combination of these circumstances recently arose twice in the UK House of Commons. In those cases, although Prime Minister Boris Johnson did not formally lose the confidence of the House, a opposition-aligned majority was able to take control of the parliamentary timetable – against the government’s will – and create time for its Bills, which were eventually passed. [1]

So far, this has not happened Malaysia. Even during the RUU 355 controversy, then-opposition MP Hadi Awang did not wrest control of the timetable to table his Bill. Instead, he was given an opportunity by the government to table a Standing Order 49 Private Member’s Bill motion without it being objected to. [2]

Had the government not approved of his tabling, a Minister would have been authorised under the Standing Orders to table a motion to either re-allocate parliamentary time under SO 14, or simply to bring the sitting to a close under SO 12.

Effectuating the Proposed One-Day Sitting

For the government to give effect to its plan of a curtailed parliamentary sitting through parliamentary procedures, it would have to pass at least one, but more likely two, procedural motions.

The simplest possibility, involving only one motion, is if the government seeks to limit the session to the YDPA’s speech, to the exclusion of even its own bills. As ‘messages from the Seri Paduka Baginda Yang di-Pertuan Agong’ is near the head of the default order of business (preceded only by the entry of the Speaker, prayers, and the taking of oaths by new members), a Minister may table a motion under SO 12 that the Dewan Rakyat be adjourned after His Majesty’s speech. Alternatively a motion to the same effect could possibly be tabled under SO 14, which would limit the business of the Dewan Rakyat to just the speech.

If the government seeks time to debate its own bills, a motion under SO 14 would also be required to adjust the order of business. Otherwise, Minister’s questions and urgent motions would have precedence over debates on bills.

However, in both cases, the government must pass a motion under SO 12 to adjourn the Dewan Rakyat in order to limit the sitting to one day. Ordinarily, the Dewan is adjourned at the end of a parliamentary day either at 5:30pm by operation of SO 12(1), or at a different time under a SO 12 motion. Where such a motion is tabled at the end of business before 5:30pm, it usually takes the form:

That under Standing Order 12(1), the House do adjourn until [time and date of next scheduled sitting].

More frequently, the motion to adjourn the Dewan is tabled together with an implicit SO 14 order of business motion earlier on in a day’s sitting as a combined programme motion. In such cases, the day’s adjournment is conditional on the conclusion of the government’s specified order of business. For example, the combined programme motion on 17 October 2018 stated: [3]

That under Standing Order 12(1), the House not be adjourned until debated and voted on are the Hire-Purchase (Amendment) Bill 2018 and the Children and Young Persons (Employment) (Amendment) Bill 2018 at No 1 and No 2 on the Order Paper for today, and then that the House do adjourn until 10am Thursday, 18 October 2018.

However, at the end of a ‘session’, the motion takes a different form since the House is not to reconvene on the next day or at a specified date in the future. Instead, it is to be adjourned sine die (i.e. without a date). In these cases, it takes the form:

That under Standing Order 12(1), the House… do adjourn until an unspecified date.

Hence, in any case where the government seeks, through parliamentary procedure, that the House does not continue to convene, it must muster a majority to pass a motion to adjourn the Dewan Rakyat sine die. [4]

The Dewan Rakyat as an Autonomous Actor

Consequently, if the Perikatan National government seeks to follow through with its plans for a one-day sitting by passing a motion in the form stated above, it must ensure that there is no opposition majority which would vote it down.

If there is a majority of MPs which objects to the government’s truncation of the parliamentary timetable, that majority is fully within its powers to prevent the government from doing so.

This is as under the Constitution each House of Parliament is designated a distinct and co-equal role to the Executive. Although the government of the day almost always has control over the Dewan Rakyat for the reasons described at the start of this post, its control is with the Dewan Rakyat’s consent and not by right. If most of the Dewan Rakyat’s members seek not to accede to the government’s control over its business, they are entitled to resist and control the order of business themselves.

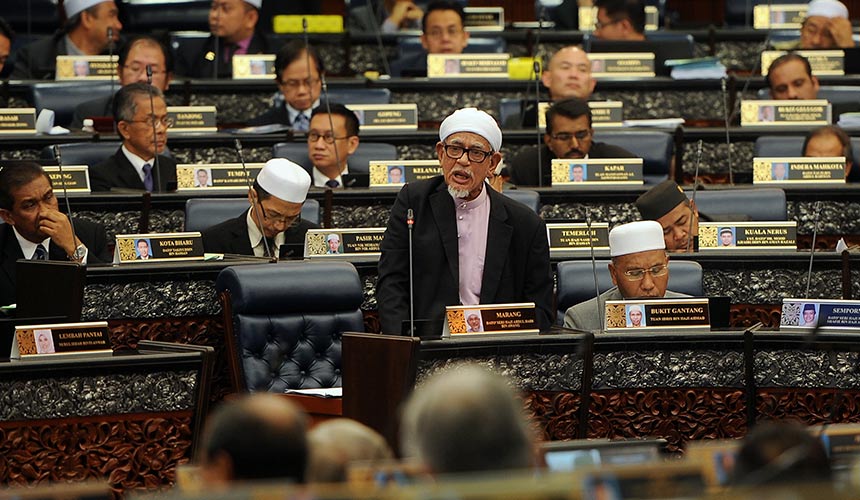

Prorogation

As Wei Jiet’s post intimated, there is a second means by which a parliamentary session can be terminated, and that is by prorogation. In contrast to an adjournment sine die, prorogation is not a voluntary act of the Dewan Rakyat. Rather, article 55(2) confers the power to prorogue to the YdPA who, under article 40(1), is bound to exercise it on the advice of Cabinet. As such, the power to prorogue is vested in the Executive, and prorogation is an act of the Executive done on the Legislature.

The existence of the power to prorogue in Malaysian parliamentary procedure is an artefact of the Westminster system, where it has its historical origins as a royal prerogative held by the British Monarch. [5]

Its anachronism in the context of the Malaysian constitution is demonstrated by the fact that its main function in Westminster systems generally is to ‘[quash] unfinished business before the Houses [of Parliament]’, [6] the most important aspect of which being the lapsing of unpassed Bills which have not been expressly ‘carried over’. [7]

In Malaysia, however, article 55(4) (added by a constitutional amendment in 1984) provides that ‘A Bill pending in Parliament shall not lapse by reason of the prorogation of Parliament’. Additionally, although another significant effect of prorogation is to terminate committee appointments and proceedings, this would have been relatively immaterial in Malaysia given the absence of an extensive system of parliamentary committees.

The elision between adjournment and prorogation in Malaysia was touched on by the Federal Court in Dato’ Dr Abd Isa bin Ismail v Dato’ Abu Hasan bin Sarif [2013] 2 MLJ 449, where the majority and minority disagreed on whether a prorogation was necessary to separate ‘sittings’ of the Kedah State Legislative Assembly, or whether an adjournment was sufficient. The central point of confusion was the ‘tradition’ [8] that, following adjournments sine die, sittings of the SLA were reconvened following a summons by HRH The Sultan of Kedah.

Speaking for the majority, Zulkifli CJM adopted the approach that a summons had the effect of implicitly terminating the preceding session to the same effect as a prorogation, even though it had only been adjourned and but not expressly prorogued by HRH The Sultan of Kedah. [9]

Dissenting, Zainun Ali FCJ took a more conventional approach and reasoned that prorogation cannot be ‘inferred, implied, or deemed’ as it is a positive act of the ruler acting on executive advice. [10] As such, adjournments – even those of an indefinite length – did not have the effect of creating legally distinct ‘sessions’ or ‘sittings’. [11]

Nonetheless, the Court’s disagreement on whether a prorogation can be implied broadly is immaterial for our current purposes. It merely demonstrates that prorogation has not played a significant role in the contemporary practice of Malaysian legislatures.

Can the government prorogue Parliament if it cannot pass an adjournment motion?

As in Abd Isa Ismail, there is a legally relevant difference between when Parliament is adjourned or prorogued. At the heart of the difference is the issue of whose decision it is for Parliament to cease sitting. Houses of Parliament adjourn themselves, but Parliament is prorogued by the Executive. Ipso facto, the Dewan Rakyat cannot be adjourned against the will of its majority, but can be so prorogued.

This distinction impacts the relevant constitutional analysis. Where Parliament deliberately decides not to sit, it is not deprived of a desired opportunity to exercise its constitutional functions, whether that be legislative deliberation or holding the Executive to account.

Legally, it is also unlikely that a court will find itself empowered to quash a motion to adjourn, since the Dewan Raykat’s decision to adjourn would fall squarely within the realm of parliamentary privilege under art 63(1) of the Federal Constitution. In the exceedingly unlikely event that such a motion is quashed, the factual existence of a majority to pass it in the first place remains, and a subsequent motion would likely be passed in its place.

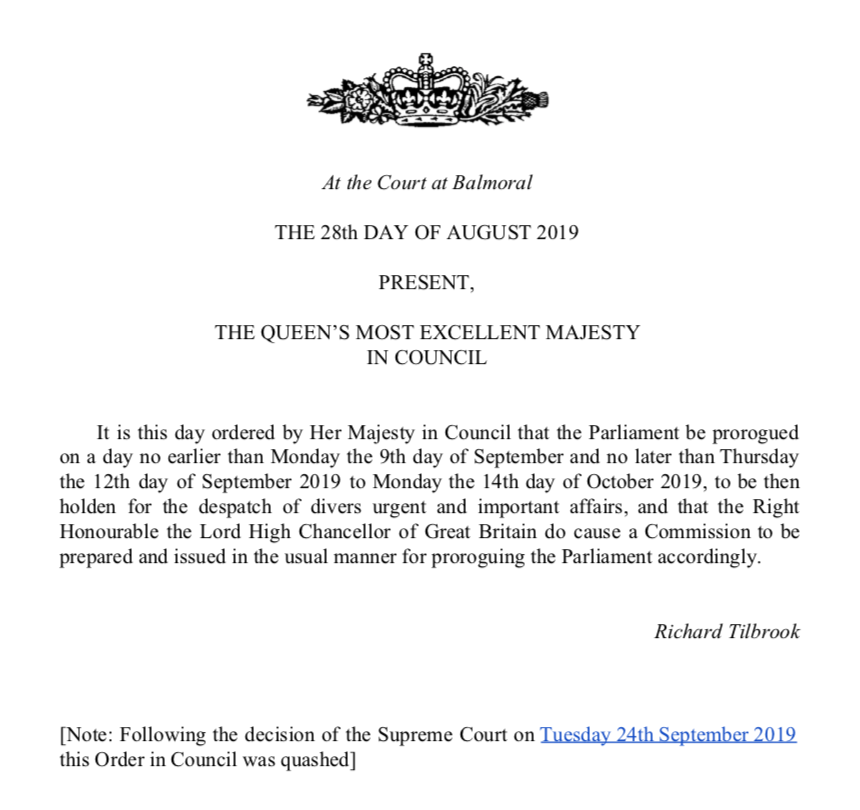

However, the constitutional analysis is different where a government does not have a majority to adjourn the Dewan Rakyat but seeks to avoid scrutiny by proroguing Parliament. It was this tension between the Legislature and Executive that arose in the United Kingdom case R (Miller) v Prime Minister [2019] UKSC 41.

In Miller, the United Kingdom Supreme Court recognised that Prime Minister Boris Johnson’s advice to the Queen to prorogue Parliament had the effect of ‘prevent[ing] the operation of ministerial accountability to Parliament’. [12] Since ‘political accountability’ was part of a fundamental principle of the UK constitution, an act which prevented it requires ‘reasonable justification’. [13] As the Court found that the government did not provide a sufficiently reasonable justification, it held that the advice to the Queen to prorogue Parliament was made without legal authority. Consequently, the Order in Council which gave effect to the unlawful advice was void.

Although Miller should not be cited as authority before the Malaysian courts due to the substantial differences in Malaysian and UK constitutional law, its broad principles are applicable just the same.

The most significant difference between the Malaysian and UK constitutions is that the UK has a sovereign parliament with plenary legal authority. In contrast, the supreme authority in Malaysia is the Federal Constitution, which sits above even Parliament.

The Court in Miller derived the principle of ministerial accountability from the more foundational constitutional principle of parliamentary sovereignty. It reasoned that: [14]

The sovereignty of Parliament would, however, be undermined as the foundational principle of our constitution if the executive could, through the use of the prerogative, prevent Parliament from exercising its legislative authority for as long as it pleased.

Naturally, this line of reasoning cannot be directly transplanted into Malaysian law as our Parliament is not sovereign. Yet, even in our circumstances, the relevant principles are still operative. At the core of Miller is the basic proposition that, in a system with a separation of powers between the Executive and Legislature where the Legislature is tasked with holding the Executive to account, the Executive cannot unilaterally exercise its powers to frustrate the Legislature from holding it to account. There is no reason why this should not also be true under Malaysian constitutional law.

In Indira Ghandi v Pengarah Jabatan Agama Islam Perak [2018] 1 MLJ 545, the Federal Court affirmed that the separation of powers is part of the basic structure of the Federal Constitution, which cannot be abrogated even by a constitutional amendment. [15] Although the case turned on the nature of judicial power, the Court still reasoned on the premise that the Malaysian conception of the separation of powers is based on the ‘Westminster model’ of constitutionalism, where the sovereign power is shared between the co-equal branches of government. [16]

It stands to reason that even though the Malaysian Parliament is not sovereign in the UK’s sense of the term, its role within the Malaysian constitutional settlement is built on the Westminster model’s understanding of a legislature’s functions. At the heart of those functions – alongside legislating per se – is holding the government of the day to account.

Accordingly, in a case where the Malaysian government seeks to frustrate parliamentary accountability by proroguing Parliament, the essential constitutional tension identified by the UK Supreme Court in Miller still exists – notwithstanding substantial constitutional differences between the two legal systems.

If the Executive seeks to significantly curtail Parliament’s ability to hold it to account, the Malaysian courts should require the Executive to supply a reasonable justification for doing do. Under this hypothetical, the presumed fact that the government is not able to pass an adjournment motion exacerbates the unconstitutionality of such an attempted prorogation.

Conclusion

Under the separation of powers which lies at the heart of the Federal Constitution, each branch of government is given powers according to its roles and responsibilities. Those powers are, however, subject to limitations, which are either legal or political in nature. Limitations of both kinds are equally important.

As the source of democratic legitimacy and locus of political accountability, Parliament has an essential role in acting as a check on the Executive. Accordingly, the Executive cannot unilaterally prevent Parliament from scrutinising it. If the government tables a motion restricting the Dewan Rakyat’s sitting to a single day, an opposing majority of MPs would be wholly entitled to reject it. If it fails to secure an adjournment, the courts have strong grounds to nullify a prorogation that is clearly designed to frustrate parliamentary accountability.

References

[1] See HC Deb 3 Apr 2019, vol 657, col 1058 on the amendment to a the programme motion which created time for the EU (Withdrawal) Act (also known as the Cooper-Letwin Act), and HC Deb 3 September 2019, vol 664, col 81 on the procedural motion which created time for the EU (Withdrawal) (No 2) Act (also known as the Benn Act).

[2] DR Deb 6 Apr 2017, p 30.

[3] DR Deb 17 Oct 2018, p 21.

[4] Parliament of Malaysia, ‘Glossary’ https://www.parlimen.gov.my/glosari1.html?&lang=en, Accessed 12 Apr 2020.

[5] Anne Twomey, ‘Prorogation’, in The Veiled Sceptre (CUP 2018), p 584.

[6] ibid.

[7] Mark Hutton and others, Erskine May: Parliamentary Practice (25th ed, 2019), para 8.6.

[8] Abd Isa Ismail [74] (Zainun Ali FCJ).

[9] ibid [15]-[16] (Zulkefli CJ).

[10] ibid [91].

[11] ibid [89].

[12] Miller [33]

[13] ibid [58].

[14] ibid [42].

[15] Indira Ghandi [39], [90] (Zainun Ali FCJ).

[16] ibid [32], approving Mohammad Faizal bin Sabtu v Public Prosecutor [2012] SGHC 163.