“Humour can be dissected, as a frog can, but the thing dies in the process and the innards are discouraging to any but the purely scientific mind. When a satirist is sued and a court attempts to ‘dissect the frog’, everyone tends to look foolish except the satirist.”

– EB and Katharine S White, A Subtreasury of American Humour.

There is recent debate in the Malaysian Twitter space (Twitterjaya) on whether satire is fake news and should be banned. This heated debate arose after the Selangor NGO Coalition lodged 3 police reports against a parodical Twitter account by the name of BermanaMY, whose parodical identity emulates the Malaysian National News Agency’s abbreviation, BERNAMA.[1]

The NGO claims that BermanaMY’s resemblance to the popular news agency is misleading and should be held liable for publishing fake news.[2] The NGO even claimed that this act of parody “will cause anxiety and tension among the people that will eventually threaten national security”.[3]

On surface, this may sound agreeable. But a deeper understanding of the intersection between satire and fake news suggests otherwise. This article will discuss this intersection as follows: (i) the general concept of satire and parody; (ii) the Malaysian treatment of satire; (iii) the foreign understanding of satire and parody; and (iv) the intersection between satire and fake news.

Credits: The Tapir Times

Humour with an Edge – The Ethos of Satire and Parody

Satire is a genre of literature driven with the intent of criticising individuals, corporations, government, or society itself to improve themselves. One of the most common forms of satire is parody, where humour is derived from a distorted imitation of a certain object. Essentially, the art of parody lies in the tension between a known original and its parodic twin.[4]

Aristophanes (popularly known as the Father of Comedy) used both satire and parody to criticise Athenian politicians. In the US, satire targeting Presidents such as George Washington, Abraham Lincoln and Franklin D. Roosevelt have always been part of its democratic tradition.

History has shown that satire is one of the best tools to ruffle a politician’s feathers. It employs sarcasm, irony and ridicule to deride prevailing vices or follies. It is capable of tearing down facades and unmasking hypocrisies.[5] Indeed, nothing is more thoroughly democratic than having the high-and-mighty lampooned and spoofed.[6]

Satire is also an effective tool to ensure robust debate on public issues. Even if such debate is triggered through “vehement, caustic, and sometimes unpleasantly sharp attacks on government and public officials”,[7] satire should not be outlawed merely because it offends the government and its officers. In fact, it is critical that these very people be subjected to a higher degree of criticism because they are accountable to the people.[8]

The Taste (or Distaste?) for Satire and Parody in Malaysia

What is the Malaysian take on satire and parody? Do we stomach such critical expression, or is it too pedas (spicy) for our taste buds?

Article 10(1)(a) of the Federal Constitution, the supreme law of the land, prescribes the right to free speech. This one provision is the genesis to media freedom, symbolic speech and the right to information.

No doubt, every right comes with restriction. Article 10(2)(a) authorises Parliament to impose restrictions on free speech on eight grounds, one of which includes public order. Parliament has promulgated a multitude of legislations limiting free speech, such as the Sedition Act, the Communications and Multimedia Act (CMA) and the Printing, Presses and Publications Act (PPPA). In such Acts, there are provisions which may on first glance indirectly outlaw fake news.[9]

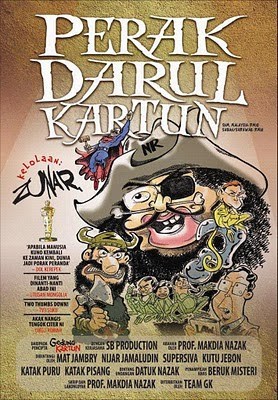

However, our Courts have in recent times protected satire in Malaysia. In Sepakat Efektif v Menteri Dalam Negeri.[10], the Minister banned a compilation of satirical cartoons on the Perak MB Crisis drawn by Zunar and various other artists, on grounds that they are prejudicial to public order and are seditious. The Court of Appeal had to decide: “to what extent can political cartoons be construed as being prejudicial to public order”?

Credits: zunar.my

In quashing the Minister’s ban, Mohd Ariff JCA (as His Lordship then was) commented on the nature of satirical work. His Lordship observed that the proper approach courts must take when assessing parodies and satires is that “if parody does not prickle it does not work”.[11] The Courts must not be too anxious to defend the person taking offence, as parody is meant to be critical in nature. Also, a fundamental understanding on the right to express is that public officers and the administration must always be open to criticism, even if it means being made fun of through satire and parody.[12]

His Lordship also took note that if an expression of thought is to be considered dangerous and prohibited, such danger must not be remote or far-fetched, but instead should have proximate and direct nexus with the expression.[13]

In fact, he also took note that cartoons aren’t sober works of literature which demand high concentration and seriousness. Cartoons like these are intended to exaggerate, satirise and parody life. Satirists like Zunar would seek to ridicule persons and institutions with humour to deliver a message.

While the cartoons were admittedly rude, the Court of Appeal ruled that it was not possible to ban them on the ground of prejudice to public order. The Court even recognised that parody is supposed to sting, and that the criticism of public administration through satire should not be viewed as a threat to public order.

Although Malaysian jurisprudence on satire and parody is rather scant, the analysis of the Court of Appeal above rebuts the claim that it is not free speech protected under our Constitution.

The Grass is Greener – American and European Appreciation of Satire and Parody

To have a more holistic understanding of satire and parody, it is necessary to explore beyond our shores and dive into US and European jurisprudence.

In the US, the classic case on satire is Hustler Magazine v Falwell.[14] Hustler Magazine featured a “parody” claiming that Falwell, a Fundamentalist minister, had a drunken incestuous relationship with his mother. Falwell sued to recover damages and was awarded a total of $150,000, to which Hustler Magazine appealed.

The US Supreme Court held that public figures and officials cannot recover damages for emotional distress without first proving that the publication contains a false statement made with actual malice. The court recognised that the free flow of ideas must be protected, even if it means the possibility of negative emotional impact on the target of ridicule. This is even more so if the person is a public official, who has to endure a higher degree of criticism.

The Supreme Court went on to observe that a parody—which no reasonable person would suspect to be true—was an expression protected under the right to free speech. The Hustler parody was not excluded from the protection of the First Amendment even though it was offensive or shocking.[15]

Credits: Alchetron.com

In Europe, the European Courts of Human Rights (ECtHR) had indicated that satire is an expression that is protected under Article 10 of the European Covenant of Human Rights (ECHR).[16] Vereinigung Bildender Kunstler v Austria concerned an artist’s paintings being prohibited from exhibition as they contained collages of politicians portrayed in sexual poses and activities with one another.[17]

Despite that, the ECtHR ruled that such expressions are necessary for a plurality of opinions and exchange of ideas, and that a democratic society needs not only favorable and inoffensive opinions and ideas, but also ones that “shock, offend or disturb the State or any other sector of the population”. The ECtHR also emphasised that “satire is a form of artistic expression and social commentary and, by its inherent features of exaggeration and distortion of reality, naturally aims to provoke and agitate”. Therefore, any interference with an artist’s right to such expression must be examined with great care.

The Good Type of Fake – Satire and the Realm of Fake News

What then is the intersection between satire and fake news?

It is without dispute that satire has the inherent feature of exaggerating and distorting reality. This intentional falsity by the satirist is to evoke reaction from society. However, even though satire presents factual falsity at its surface, it is not meant to be judged at face value and appreciated in a literal sense. Satire, underneath its sheet of factual falsity, conveys a critical message. The audience who appreciates this feature of satire would read satire contextually and not literally, and understand that it is more of an opinion than a statement of fact.[18] In fact, in US jurisprudence, statements of opinion can never be regarded as false since there is no such thing as a false idea.[19]

Credits: Saturday Night Life

Even if it is hard to agree that an opinion cannot be rendered false, there is still much value in a false statement. John Stuart Mill, renowned jurist, took the view that false statements can also make valuable contribution to public debate as it generates a “clearer perception and livelier impression of truth, produced by its collision with error.”[20]

In essence, this statement reflects the ‘marketplace of ideas’ theory, which postulates that in free and public discourse, all ideas—including false ones—should be available to the community because a restriction on speech of any kind may incidentally restrict the truth.[21] It holds that without government interference, truth and falsity will compete in the marketplace, and truth will emerge victorious. And within this marketplace of ideas, it may be argued that no false statement is more valuable than humour, satire, parody and mockery.[22]

The intersection of fake news and satire has been critically examined in two different US cases. The first is New Times Inc v Isaacks,[23] where a judge and district attorney sued an “alternative weekly” newspaper after they were satirised in an article published in response to the controversial arrest of a minor on terroristic charges. The Texan Supreme Court held that a reasonable reader should not be capable of confusing the satirical expression with real news. This is because an objective reading of the content would show that a hypothetically reasonable reader could not possibly be misled. The court also noted that the satirist’s ‘intent to ridicule’ could not be construed as ‘actual malice’, as that would curtail the robust public debate that the satirical expression intended to evoke.

A similar principle was echoed in San Francisco Bay Guardian v Superior Court.[7] Here, the court held that a newspaper’s April Fool’s Day parody edition was protected under the First Amendment, even though it contained a fake letter attributed to a real person. The court observed that the satirical nature of the newspaper should have been clear to an average reader viewing the ‘totality of the circumstances’. Viewed in its full context, it would be obvious to the average reader that the letter was a parody.

Therefore, it is clear that satire should not be perceived as another species of fake news. This position is similarly reflected within the Malaysian Communications and Multimedia Content Code, where item 7.3 states that all false content is prohibited except fiction, satire and parody.[24]

Conclusion

Satire and parody are valuable mediums to hold the powers-that-be accountable for their vices, scandals, follies and misdemeanours. It is a uniquely entertaining yet critical tool which may evoke societal attention on matters of public interest. Although it may be sarcastic and ironic, satire and parody is by no means fake news. The falsity behind satire serves a useful purpose, and it should not be faulted just because a select few lack the aptitude to appreciate its satirical nature.

Malaysia is no stranger to acts of satire and parody. In fact, BermanaMY is not the first Malaysian parodical news account to be created. Social media users may be familiar with TheTapirTimes and Astro AWATNi, both of which are parodical news accounts which report satirical news ridiculing the many issues gaining traction in the Malaysian social media landscape.

The “news” report by BermanaMY which the 3 police reports were made against is the following:

Credits: Twitter user @faizalzulkefle

The content of the report shows an intent to mock and ridicule the Minister mentioned. It would be ridiculous to assume that any government would want to ration food supplies only on the basis of “avoiding obesity” during a global pandemic. Unless it is already so normal for Malaysians to receive such ludicrous governance, the satire in this report is clearly visible.

Ever since the police reports were lodged, BermanaMY has changed its account name to BawangMana. At the end of the day, BermanaMY is clearly distinguishable from BERNAMA at first glance. Like other parodical accounts, BermanaMY avoided emulating the BERNAMA News Agency entirely. BermanaMY designed a separate logo and coined a distinctive username. Even its page’s description indicate clearly that it is only a parody account. It would be an insult to the intelligence of our people to claim that the Malaysian citizens may confuse BermanaMY for BERNAMA.

The reluctance of fact-checking and performing our share of due diligence is not an excuse to expel all forms of satire and parody. Even if we were to purge all forms of satire in Malaysia, we are still very much exposed to foreign satirical content. Hence, the lesson to be learnt here is that we must not attempt to escape satire and parody. Rather, we should learn to appreciate its thorny embrace.

Satire has played its role well in Malaysia. We all know zesty Zunar, who has diligently illustrated the most ridiculous aspects of Malaysian politics through his witty and sharp cartoons. We know of Fahmi Reza and his defiant clown caricature of Najib Razak, which became an icon of the national fight against kleptocracy. These satirists have sparked nationwide debates on issues which matter to the Rakyat. They found solace in these works of satire, which echo their frustration and angst towards the government on various issues. They contributed greatly to the empowerment of the people, which in the end culminated in Malaysia’s first change of government ever since independence.

Indeed, the words of celebrated American journalist Molly Ivins ring true: “satire is traditionally the weapon of the powerless against the powerful”. We must protect this weapon, and not treat it as a scapegoat of our ignorance.

References

[1] Three police reports lodged against BermanaMY. (2020, April 21). BERNAMA. Retrieved from https://www.bernama.com/en/general/news.php?id=1834443

[2] Ibid.

[3] Ibid.

[4] In re Callahan 238 W. Va 495.

[5] Treiger, L. K. (1989). Protecting Satire against Libel Claims: A New Reading of the First Amendments Opinion Privilege. The Yale Law Journal, 98(6), 1215. DOI: 10.2307/796578

[6] Ibid.

[7] New York Times Co. v. Sullivan, 376 U.S. 254 (1964).

[8] Ibid.

[9] S. 504 & s. 505 Penal Code; S. 8A PPPA; s. 233 CMA; s. 4(1) Sedition Act.

[10] [2014] MLJU 1874.

[11] Laugh it Off Promotions CC v South African Breweries International (Finance) Case (2005) 5 LRC 475

[12] Leonard Hector v AG of Antigua and Barbuda [1990] 2 WLR 606.

[13] S. Rangarajan v P. Jhagivan Ram & Ors [1989] 2 SCC 574.

[14] 485 U.S. 46 (1988).

[15] The First Amendment of the United States Constitution protects the right to freedom of religion and freedom of expression from government interference.

[16] Eon v France (Application No. 26118/10); Kulis and Rozycki v Poland (Application No: 27209/03) [2009] ECHR 1456; Alves da Silva v Portugal (Application No: 41665/07).

[17] (Application no. 68354/01) 25 January 2007.

[18] Supra at note 5.

[19] Gertz v Robert Welch Inc. 418 U.S. 323 (1974)

[20] Gutterman, R. S. (2014). Contributing Article: New York Times Co. v. Sullivan: No Joking Matter – 50 Years of Protecting Humor, Satire and Jokers. First Amendment Law Review – UNC.

[21] Ingber, S. (1984). The Marketplace of Ideas: A Legitimizing Myth. Duke Law Journal, 1984(1), 1. DOI: 10.2307/1372344

[22] Supra.

[23] 91 S.W.3d 844 (Tex. App. 2002).

[24] (2001) 94 Cal.App.4th 963.

[25] Malaysian Communications and Multimedia Content Code, Item 7.3.